Nasogastric Tube Placement

Although it is common to see patients with a myriad of tubes, catheters and monitors all over the body, the nasogastric tube is a simple option that should be considered sooner and more frequently for both straightforward and complex diagnoses alike. The nasogastric tube offers multifunctional support by way of providing comfort, alleviating nausea and evacuating gastric fluid in patients with gastrointestinal stasis while providing the option to deliver essential nutrition and medications. All of this in a tool that is relatively inexpensive and easy to place. The cost may be offset by decreased time in the hospital in some patients.

This discussion will review disease processes that would benefit from the placement of a nasogastric tube, will outline protocols for placement and maintenance, will discuss complications and contraindications to consider, will provide the calculations for nutritional requirements and then will discuss three cases from Capital District Veterinary Referral Hospital that all greatly benefited from the placement of a nasogastric tube.

Historically, feeding tubes were considered in patients with oral trauma or hepatic lipidosis but this technique should also be considered for patients with gastrointestinal illness, metabolic disease or any process that can render a patient inappetent. Even with patients that are vomiting, NG tubes may help with evacuation of gastric fluid, even if they are not ready to be fed or medicated using the NG tube.

As recently as a decade ago, it was still considered recommended practice to fully fast dogs and cats suffering from vomiting, diarrhea, gastrointestinal inflammation, and pancreatitis. This has proven to increase the risk for bacterial translocation, delays healing and recovery, exacerbates hypoproteinemia and may increase complications and increase the duration of hospitalization. With the use of an enteral feeding delivered by the non-surgical placement of a nasogastric tube, it is possible to counter these concerns while providing nutrition to the enterocytes in the small intestine, reducing the risk for bacterial translocation and many patients will eat sooner after tube placement then without placement (JVIM, 2008).

Consider using this supportive measure in patients with post-operative ileus, parvoviral enteritis, pancreatitis, septic peritonitis, regurgitation, GI stasis, severe emaciation and with some neurologic conditions. Patients that are not eating 50% of their RER in three days should be considered for NG tube placement. It is important to include the days prior to presentation in this assessment of duration of inappetence. Force feeding is not recommended as this may lead to food aversion, aspiration pneumonia and will likely not meet the nutritional requirements of the patient.

Contraindications to placement of a nasogastric tube includes patients that are vomiting frequently, are comatose, do not have a gag reflex, patients that are severely dyspnic, and patients that have nasal disease or a nasal mass. Patients that are profusely vomiting or have a gastrointestinal obstruction may have a tube placed for evacuation of gastric fluid but feeding through the tube would be contraindicated until the vomiting or obstruction were resolved. If the tube is vomited out, it may be replaced, however placement radiographs must be performed every time the tube is repositioned or replaced.

Complications:

Complications include placement of the tube in the trachea or bronchi, aspiration pneumonia secondary to vomiting, regurgitation or tube dislodgement, epistaxis from irritation of the nasal mucosa, vomiting and regurgitation. Fluid losses and electrolyte imbalance may be secondary to removal of large volumes of gastric fluid from ileus but can be balanced by replacement therapies using intravenous fluids and electrolyte supplementation. Recent findings suggest that there was no increased risk for hypochloridemic alkalosis in patients with NG tube placement (JVECC, 2018).

There are many textbooks, journal articles and video references to review the techniques for placement of the nasogastric tube. One resource that may be helpful is VetBloom, providing online veterinary courses and continuing education. The following information outlines the techniques and recommendations found on VetBloom. It is imperative that the tube placement be assessed using radiographs. Minimally, a lateral view but optimally, two view radiographs should be utilized for best assessment and least possible complications or malplacement, given the gravity of disease and complication should the tube be placed in the trachea and/or bronchi.

Documentation:

Record the date, time and staff member placing the tube. Include the tube type, length, diameter and nostril, right or left. Record the placement verification by radiograph and/or radiologist review, tube aspiration (negative pressure or stomach contents) and tube auscultation (positive or negative). Prior to starting the enteral nutrition, document radiographic placement/radiologist review, tube aspiration and auscultation and test injection of water (cough, gag, retching-yes or no).

Materials:

1. 3-5 drops of tetracaine or proparacaine (also can use 1-2cc of 2% lidocaine)

2. Sterile lubricant jelly

3. Appropriately sized tube: a. 8-10 Fr polyurethane or medical grade silicone nasogastric tube (8 for cats and small dogs, 10 for larger dogs) b. 8 Fr long red rubber tube (large dogs) – likely only long enough for NE placement c. Mila tubes- 6Fr x 55 cm or 8Fr x 108 cm Mila weighted feeding tubes

4. 3-0 nylon suture material

5. Needle drivers and scissors and/or 22-gauge needle

6. Permanent marker

7. 1-inch white tape 8. Empty 3cc syringe and a 3cc syringe with 1cc sterile water

Procedure:

1. Gather the materials needed as listed above.

2. Apply 3-5 drops of local anesthetic down the nostril to be used while the nose of the patient is elevated. This ensures distribution of the drug evenly on the mucous membranes that line the nasal cavity. Allow 4-5 minutes for the drug to properly anesthetize the area.

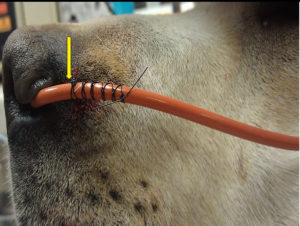

3. This is a good time to place your suture to be used for securing the tube with a finger trap after placement. To do so, place the 22-gauge needle through 1/8 inch of skin at the junction of the wing of the nostril and the fur with the point of the needle directed dorsally. If this is done quickly most animals do not resist. The needle may be left in place while the suture material of 3-0 nylon is grasped.

4. Pass the end of the nylon suture through the pre-placed needle in the skin. In order to be able to remove the needle, the suture material must be passed from the beveled tip towards the hub. Once the nylon suture comes through the hub of the needle, grasp the suture material and adjust the nylon until equal amounts are on either side of the skin attachment. Now removed the 22-gauge needle by pulling it off the nylon.

5. With equal amounts of nylon on either side of the skin attachment, tie a square knot in the nylon being sure that the suture is loose. This allows anchoring of the tube with minimal pressure and irritation to the underlying skin.

6. Now measure the tube from the tip of the nose to the appropriate landmark: a. If placing an NE tube, measure to the 9th rib and mark the tube or note the cm on the premeasured tubes. b. For an NG tube measure to the last rib and mark the tube or note the cm on the premeasured tubes.

7. Liberally lubricate the tip of tube with sterile lubricant jelly.

8. Grasp the animal’s muzzle firmly with your non-dominant hand.

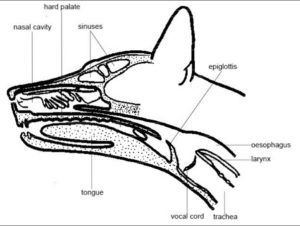

9. Using your dominant hand introduce the tube into the ventromedial (ventral and medial line of nasal passages) aspect of the nasal cavity through the selected nostril. a. Brace the introducing hand against the animal’s muzzle so that the hand moves with the animal’s head when it moves or sneezes. Release the tube when the animal moves so you don’t pull the tube out. b. Use short controlled insertions when inserting the tube. Release the tube between insertions. Allow the animal to settle before inserting again. c. When the tube reaches the median septum, push the animal’s nose dorsally with your thumb to open the ventral meatus (opening) (see picture below.) d. If the tube passes into the dorsal nasal cavity it should be removed and re-inserted more ventrally.

10. Hold the head and neck in a neutral position as you advance the tube. As the tube passes through the oropharynx into the esophagus, the animal may or may not swallow. Massaging the throat may stimulate swallowing and encourage proper placement of the tube.

11. When the tube is advanced to the appropriate distance, aspirate the tube using the syringe. If air is aspirated, then the tip of the tube may not be in the esophagus/stomach and the tube may need to be removed and re-inserted. If the stomach is gas-filled, you should expect to aspirate air. Smelling the aspirated air may help differentiate between proper and improper placement. If nothing is aspirated, continue to advance the tube. If the animal coughs or if the tube comes out the mouth or other nostril, remove the tube and re-insert it. Remove the tube if the animal coughs at any time during insertion. NOTE: the lack of a cough does not mean that the tube is not in the trachea.

12. If the tube is styletted, remove the stylet at this point.

13. Position the tube over the pre-placed square knot at the level of the indelible mark and begin the Finger Trap pattern around the tube. A minimum of 5 crosses is essential to secure the tube. Do it correctly the first time. This will save time and patient inconvenience during therapy.

14. Direct the tube to the side of the animal’s head. Place a tape butterfly on the tube and secure to the side of the animal’s head under the ear with suture.

15. Next, suture the tube to the cheek so that it is secured at two locations. Avoid the whisker area for patient comfort. An alternative path is to secure the tube between the eyes. This method should only be used if the doctor instructs you to do so. Remember to tie a loose square knot in the nylon before anchoring the tube so that the skin is not pinched. The facial nerves run across this area of the cheek so the suture should go through the skin but be kept as superficial as possible.

16. Place an E-collar on the animal.

17. Confirmation of proper placement by radiography. 2-view radiographs are required. a. The distal tip of the feeding tube should be placed between the carina and diaphragm for an NE tube and into the stomach for an NG tube. b. If the tube is going to be used to provide nutrition, the radiographs must be reviewed by a veterinary and/or radiologist prior to initiating feeding.

Troubleshooting:

The primary problem is tube occlusion. If the tube becomes occluded, then fill it with water and let it sit for 5 minutes. If it is still occluded, then aspirate and inject water forcefully a few times to dislodge a blockage. If it is still blocked, then put a small amount of Coke in the tube and let it sit for 10 minutes. If this does not work, replace the tube. Another problem is nasal irritation and discomfort and the only way to treat this is replacement of the tube in the other nostril. Sometimes, repeated use of topical anesthetics can help dull the sneezing. Excessive sneezing can cause the tube to come out. Rarely a patient can vomit up the tube. The patient then might chew the end of the tube and swallow the pieces. If the tube becomes dislodged in any way, it should be removed and replaced with a new tube.

Nutritional Calculations:

1. Calculate RER (kcal/day) as (weight (kg) x 30) +70.

2. Choose diet (Jevity has 1.5kcal/ml) and total milliliters of diet per 24 hours.

3. Calculate feeding plan-bolus feeding = diet ml/kcal/day divided by feeding/day=___ml every __hrs.

4. Calculate flush volume and frequency.

5. CRI feeding option also may be a consideration.

Maintenance of the tube should include observation and auscultation of the patient, checking the distance marker of the tube placement, aspiration of the tube, recording volume of air or fluid obtained, flushing with water or sterile saline and feeding amount and frequency with comments regarding ease of flush/feeding, patient response to feeding or flushing and any gagging, retching, drooling or coughing.

Case Reviews:

The following cases were selected based on the subjective observation of marked clinical improvement in GI signs, nausea, drooling, lethargy and malaise. The placement of the nasogastric tube to evacuate the stomach of large amounts of fluid and bile is thought to have allowed for decreased morbidity while supportive care and diagnostics were instituted.

1-GDV, post-operative ileus, IBD

A 4.5-year old, male neutered Great Dane was presented to CDVRH in November 2019 for abdominal distension, lethargy and profuse drooling. CBC and chemistry were normal apart from hemoconcentration at 58% and a mildly elevated lactate at 2.1. Abdominal radiographs revealed gastric torsion and dilation and the patient was taken to surgery for an exploratory laparotomy, de-rotation of the stomach and gastropexy. There were no other abnormal findings at surgery and no arrhythmia noted perioperatively. Post-operatively he was treated with intravenous fluids, ondansetron, metoclopramide CRI, pantoprazole, maropitant and perioperative cefazolin.

Recovery was uneventful for this post-operative GDV patient and follow up blood testing remained normal. Ultrasound showed some fluid in the stomach the day after surgery that was thought to be mild post-operative ileus. He ate 36 hours post operatively and was discharged 48 hours after surgery. However once home he stopped eating, developed diarrhea and had recurrence of drooling. Follow up examination and ultrasound found severe gastric ileus with marked amounts of fluid in the gastric lumen. He was rechecked at CDVRH, admitted and a nasogastric tube was placed. Aspiration of the tube at the time of initial placement produced 1.6 L of brown malodorous fluid. The tube was aspirated every 4 hours and showed a continued trend of a high yield of fluid with 1L 4 hours post placement, then 700ml and 900ml. Thereafter the patient became more comfortable, began eating once again, drooling ceased, and the volume of aspirated fluid dramatically reduced. This patient had baseline cortisol results that were normal, however the GI panel indicated IBD. He was treated with B12 injections, metronidazole and prednisone and the gastric stasis, drooling and inappetence resolved.

2-Severe gastric ileus, IBD

A ten-year-old, male neutered DSH presented to CDVRH November 2019 with vomiting for several days and lack of appetite. The patient had blood testing and abdominal radiographs with the referring veterinarian that revealed a large kidney but no overt abnormalities otherwise, including no azotemia, normal T4 and well concentrated urine. Despite GI supportive treatment with mirtazipine and maropitant, the patient continued to vomit and upon presentation the major concern was the profound lethargy and nausea.

Point of care ultrasound upon triage revealed a markedly fluid distended stomach with lymphadenopathy in the area of the gastric outflow, a large left kidney, a small right kidney and no obvious gastrointestinal obstruction, masses or foreign bodies. The patient was admitted for supportive care and workup. Blood testing showed azotemia with a BUN of 62, creatinine of 2.4, lactate of 2.8, alkalosis with low sodium at 145, low potassium at 3.2 and low chloride at 94. The urine culture was negative, cortisol was normal, FeLV/FIV/HW were all negative and the GI panel was indicative of IBD. Retrospectively the patient was historically fed z/d diet and was doing well but had been on a different diet for about a year. He was treated with intravenous fluids, Unasyn (urine culture pending), maropitant, pantoprazole, metoclopramide CRI, buprenorphine PRN. The placement of the nasogastric tube allowed the evacuation of 160ml of malodorous gastric fluid and the patient very quickly had less nausea, lethargy and malaise.

Subsequent nasogastric evacuation every 4 hours produced 14ml, 16ml, 96ml, 0ml, 10ml, 97ml, 3.5ml, 6ml, 52ml of gastric fluid in the first 36 hours of treatment. The patient ate well when the stomach was emptied of the fluid content and moderate fractious behavior resolved. The patient was treated with prednisolone and B12, a diet change to z/d and went on to have no further signs of illness.

3-Parvoviral enteritis

A four-month-old golden mix male puppy presented to CDVRH in September for supportive care after a parvoviral enteritis diagnosis made at his primary care veterinary hospital. He was leukopenic, had a low normal blood glucose, low normal potassium, albumin of 2.5 and a negative fecal/Giardia PCR. He was treated with intravenous fluids, potassium supplementation, maropitant, ondansetron, pantoprazole Unasyn, metronidazole and metoclopramide CRI. After 24 hours of supportive care, he remained dull, anorectic with ongoing diarrhea and the white blood cell count was dropping. A plasma transfusion was started. A point of care ultrasound showed no intussusception or foreign body, however there was fluid in the stomach, so a nasogastric tube was placed to empty the stomach and start trickle feeding. Jevity was started at one quarter RER. This puppy had marked improvement in comfort, reduced nausea and improved activity after the stomach was emptied. Despite low white blood cell count and low albumin, recovery was uneventful and return to normal activity and appetite occurred within 36-48 hours of admission.

Citations:

Effect of early enteral nutrition on intestinal permeability, intestinal protein loss and outcome in dogs with severe parvoviral enteritis, Albert J. Mohr, DVM, et al, JVIM, Volume 17, Issue 6, June 28, 2008.

Retrospective evaluation of the impact of early enteral nutrition on clinical outcomes in dogs with pancreatitis: 34cases (2010-2013), Jessica P. Harris, DVM, et al, JVECC, Volume 27, Issue 4, May 16, 2017.

Early nutritional support is associated with decreased length of hospitalization in dogs with septic peritonitis: A retrospective study of 45 cases (2000-2009), Debra T. Liu, DVM, et al, JVECC, Volume 22, Issue 4, August 28, 2012.

Incidence of hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis in dogs and cats with and without nasogastric tubes over a period of up to 36 hours in the intensive care unit. Annie Chih, DVM, et al, JVECC Volume 28, Issue 3, May 4, 2018.

Nasoesophageal/Nasogastric Tube Placement, Level 4 Protocols, VetBloom Module.

Nasogastric Feeding Tubes: The Technician’s Role, Educational Medical Lecture, VetBloom Module.