Adrenal Gland Tumors In Cats and Dogs: Diagnosis & Treatment

Written by Staff Veterinarian

What is the adrenal gland?

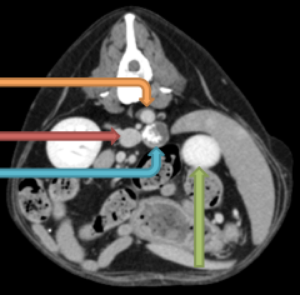

The adrenal glands are a set of paired glands found within the abdomen in cats and dogs that constitute a major portion of the hormonal (endocrine) system. The adrenal gland can be split into two major regions. The outer portion, the cortex, is responsible for producing cortisol (the main stress hormone of the body), some sex hormones, and substances which help regulate the body’s blood pressure and electrolyte balance. The inner portion, the medulla, produces adrenaline and its precursors (epinephrine, norepinephrine). The adrenal glands are located very near the kidneys and adjacent to the major blood vessels of the abdomen, the aorta and caudal vena cava.

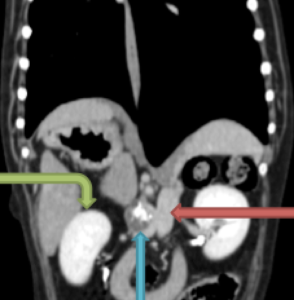

Axial view of a CT scan of the abdomen in a dog with an adrenal mass. The orange arrow indicates the aorta. The red arrow indicates the position of the vena cava. The blue arrow points to the adrenal mass. The green arrow indicates the position of the left kidney.

How is an adrenal tumor diagnosed?

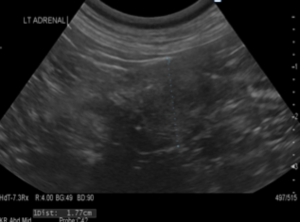

Most adrenal tumors are identified during abdominal ultrasound for evaluation of the source of symptoms caused by the adrenal tumor, or the tumors are seen incidentally when performing an ultrasound for other reasons. A mass is identified when the adrenal gland is noted to be greater than 1.5cm on ultrasound measurement. Adrenal tumors can be divided into roughly two categories: functional tumors, which are associated with increased hormone secretion, and non-functional tumors. After identification of an adrenal mass, further testing is often recommended to determine functional status, as this will improve the likelihood of a successful outcome with surgery.

Ultrasound measurement of a mass within the left adrenal gland. The mass measures 1.7 7 cm. A normal adrenal gland should be no larger than 1.5 cm in any dimension.

Masses which produce increased cortisol will often cause symptoms in animals, including increased appetite, thirst, and urination, panting, weight gain, and hair loss. Confirmation of increased cortisol production can be achieved by performing a low dose dexamethasone suppression test, a blood test which is performed over 8 hours.

Masses which produce increased adrenaline can cause sudden spikes and drops in blood pressure. This is manifested as fainting or episodes of collapse with diaexcitement. Diagnosis of these masses on physical examination can be difficult. Occasionally retinal hemorrhage or elevations in blood pressure can be documented, but more often a history of collapsing episodes is the only supportive finding. Measurement of urinary adrenaline can help strengthen the presumptive diagnosis.

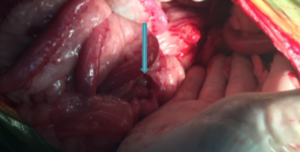

Blue arrow: Adrenal mass as seen at surgery

How do you treat tumors of the adrenal glands?

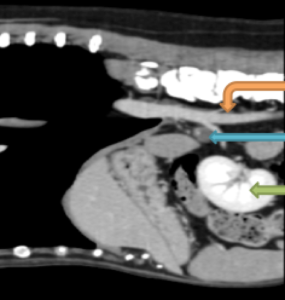

Adrenalectomy (surgical removal of the adrenal gland) is generally recommended when a functional adrenal tumor is diagnosed, or if features of malignancy are noted (enlargement of nearby lymph nodes, invasion of the mass into the blood vessels). With larger tumors and tumors with evidence of growth into a blood vessel (vascular invasion) on ultrasound, a CT scan is generally performed prior to surgery.

Sagittal (side) view on CT scan of the abdomen in a dog with an adrenal mass. The orange arrow indicates the aorta. The blue arrow is the adrenal gland. The green arrow indicates the position of the left kidney. The head is to the left.

Green: Left kidney, Blue: Adrenal gland, Orange: Aorta

What are the complications of adrenalectomy?

Due to the close relationship of the adrenal gland with the blood supply of the abdomen (aorta, vena cava), hemorrhage is always a major concern during adrenalectomy. Prior to surgery, each patient is blood typed in case a transfusion of red blood cells is needed during or following surgery.

Each type of functional adrenal mass carries its own associated risks with removal. Masses which produce adrenaline can cause sudden spikes and drops in blood pressure while the mass is being handled during surgery. Medications can be administered intraoperatively to help lessen the effect of these adrenaline releases on the heart and blood vessels. The presence of a Veterinary Anesthesiologist is very beneficial in helping to reduce the risk of significant arrhythmias which can occur during surgery, and advances in anesthetic monitoring and care after surgery have decreased the risks of surgery significantly.

Adrenal mass removed surgically

Masses which produce cortisol can cause an increase in clot formation in the body, as well as delay healing. During surgery and in the immediate postoperative period, there is a risk for embolization (lodging) of blood clots into the blood vessels within the lungs. If this happens there is impairment of the delivery of oxygen into the blood stream and the patient can have difficulty breathing which can progress to sudden death. The most recent papers suggest a mortality rate of 19-22% with surgery which is greatly improved over previous studies. Testing and medical treatment prior to surgery can help significantly reduce this risk.

Other complications can include mild electrolyte imbalances, delayed healing, coughing, and incisional complications (bruising, infection).

Chest x-ray (radiograph) of a dog with a large pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE) to the left side of the lungs. Note how the right side of the image is much more opaque, indicating a lack of air within the lung tissue.